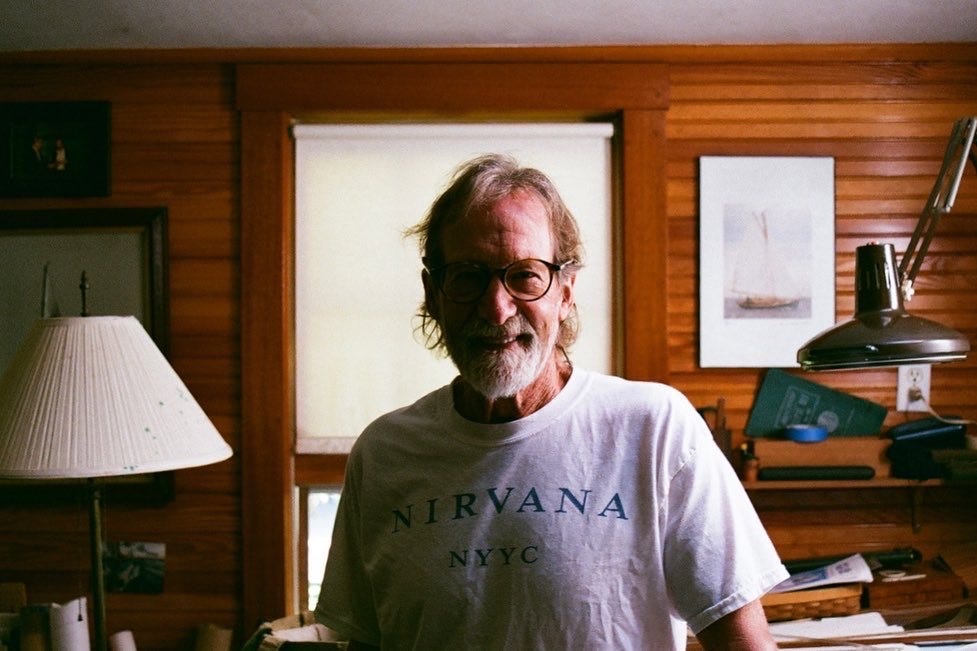

Last month, I visited my uncle, a sailor and a boat builder. He is a true craftsman, and among the happiest people I know—a man living in a paradise of his own creation.

I admire him deeply. He is focused on his craft, shameless in his pursuit of it, and unbothered by things that do not concern him. A humble and deeply considerate man, he has composed a vibrant international community of sailors scruffy and stately, artists starving and renowned, and even U.S. presidents who admire not only the boats he builds but his philosophy to building them.

He embodies the traits shared by those I admire most: they’re givers, not takers. They build things (often tangible things). They’re exceptionally curious and radically individual, and wherever they look for beauty, they either find it or cause it to be.

the desire trap

I’m unconvinced that most people really know what they want. Or if they do, they do not know why they want it. Or that, simply, too many of the things we do are simply a reaction to social convention—a reaction to a reaction. How far are your decisions abstracted from the things you really want?

Desire is often said to be the cause of pain, but really it’s ignorance. Desire by itself is only natural—the counterpart to motivation—and our desires drive us to do incredible things and help us achieve some kind of meaning.

But desire is a power easily misplaced, and this is what seems to trap people—being convinced to like something you do not really enjoy, or chase something you do not really want.

wear patterns

You cannot find happiness if you are chasing it. You cannot rationalize your way out of a feeling you know in your heart to be true. The things that are true about us are often more subtly emergent than nakedly evident. Instead of chasing after them, you have to stop and pay attention and listen closely. You must leave space for them.

Communication is the cause for the disintegration of nearly every failed relationship, including yours to yourself. The entire marriage counseling industry is centered around this critical inability to tell your significant other how you feel, or what you want, or why you’re hurting. Deliberate communication can be exceedingly difficulty—it is an exercise in parsing clarity from commotion and translating vast unsayable emotion into language.

Most of our communication is unspoken anyway. It is not deliberate—we read it through body language and intangible auras (vibes) and actions over time and evidence that emerges through thoughtless repetition.

Like Abraham Wald’s famous bullet-ridden bomber, we don’t know where to look for the things we want. Too often, we come up for air after fixedly chasing a goal only to realize that we didn’t actually want it at all.

Maybe what we want has been there the whole time, hidden in the periphery, precisely where we weren’t looking for it. Or perhaps it was right in front of us. It’s never screamed for attention and it doesn’t seem like the thing we were supposed to chase, because it doesn’t need to be chased at all.

listening closely

Werner Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle reveals that reality is inseparable from the way you observe it. At its loosest interpretation, we might begin to see that beauty really is in the way we behold it—what we find beautiful is what we give our attention to.

We love the things and the people we know the most about, and we know so much about them because we love them. This is why we tend to love those things that seem familiar, that remind us of something deep within us or our past.

We can learn to love new things too—taken this way, love is an act of learning. It is a beautiful kind of learning, one where you listen closely and open yourself with incredible vulnerability and never tire of it. This kind of learning is both unusually hardy and exceptionally delicate, capable of withstanding blow after blow and compelled to press on beyond reason, yet fouling with the first trace of uncertainty.

So, loving anything becomes an exercise in learning about it, including yourself. It’s never easy to figure this out—to cut deep through mimicry and social expectation and paths of least resistance and comfort; to learn what it is we really want.

The intention I set to underlie this year was simple: to understand myself deeply. It had gotten muddied in comparison and people-pleasing. Too many people projecting their expectations onto me; too many of my own insecurities projected onto others. Too little clarity. The decisions I was making were becoming riskier and risker—reactions to reactions, defined by what they weren’t instead of where they led.

I was building a company at its earliest (and most fragile) state, and I couldn’t really tell you why. The best answer was that I felt accountable to my team, but that wasn’t unique to the business we were building or the problem we were solving. We had achieved modest success with promise of more just around the corner, and yet my motivation had dwindled. This was the very motivation that had pushed me through countless pivots, through unbelievable tribulation and the hardest, most uncomfortable sustained effort I had ever put forth. And yet, despite withstanding blow after blow and lack of reason, it faded at just a whisper of uncertainty

Falling out of love feels a lot like falling in love—unmoored, vulnerable—but without the guarantee of a safe landing. Maybe it’s a return to your former formlessness, the reacquaintance with a blank slate. How do we start again from scratch; begin again completely?

what now?

I feel like I’ve started over so many times. Schools, places, cultures. The effort has never been duplicative or tedious, and all of the lives I’ve lived have made my life abundant. Each transition has granted me the opportunity to take account of myself, my community, my motivation, and what I really want. And I begin again with sharpened clarity, fresh conviction, and a deeper understanding of myself, the world, and my place in it.

In the spirit of starting from scratch, I’ve made 0→1 my thing. The thing I’ve always been exceptionally good at is dealing with ambiguity by taking it apart and reassembling it into something that makes sense. Building from zero takes time, significant energy, and endurance. Failure is the default outcome, clarity the high, and signal from noise the objective.

Is it a process of discovery or synthesis? Are we taking things apart of putting them together? The best way to learn is to just figure it out. So that’s what I’m doing.

Relay is a 0→1 product development team. We help brilliant founders build the products that will take their businesses to market. It’s me and five of the most talented, smart, and incredible people I’ve known.

Product is composed of three functions—marketing, design, dev—around one objective: building something valuable for a real user. Two of us specialize in each function, and all of us are generally aligned toward product. Our clients sometimes think of us as product managers with incredible execution potential, or fractional product cofounders.

The most important thing is that we’re builders. Together, we’ve built a significant portion of our university’s entrepreneurship program, founded a bunch of revenue generating businesses (branding agencies! software startups!), created historical nonprofits etc. But the thing I’m most proud of is simpler: these are the people with whom I share dinner at the end of the week, no matter what it held. These are people who are, simply, here for you.

Relay started a couple months ago, and the biggest problem it’s presented so far is that it’s growing really fast. We’re getting our hands dirty with business fundamentals—hiring, process, accounting. It’s this ‘boring stuff’ that makes it so fun, because it makes this real. Maybe this—these people, this feeling of motion—is what I wanted to whole time.

it took me to figure out how to say all of this, and it feels great to get it on paper. is this the end of the startup gap year? perhaps. is it the beginning of something far more exciting/promising? absolutely.